Words Stephen Greco Photography Carlton Davis

Artworks courtesy of © Ellsworth Kelly Foundation

Published in No 7

Revolver, North Family, Mt Lebanon, NY, ca. 1860.

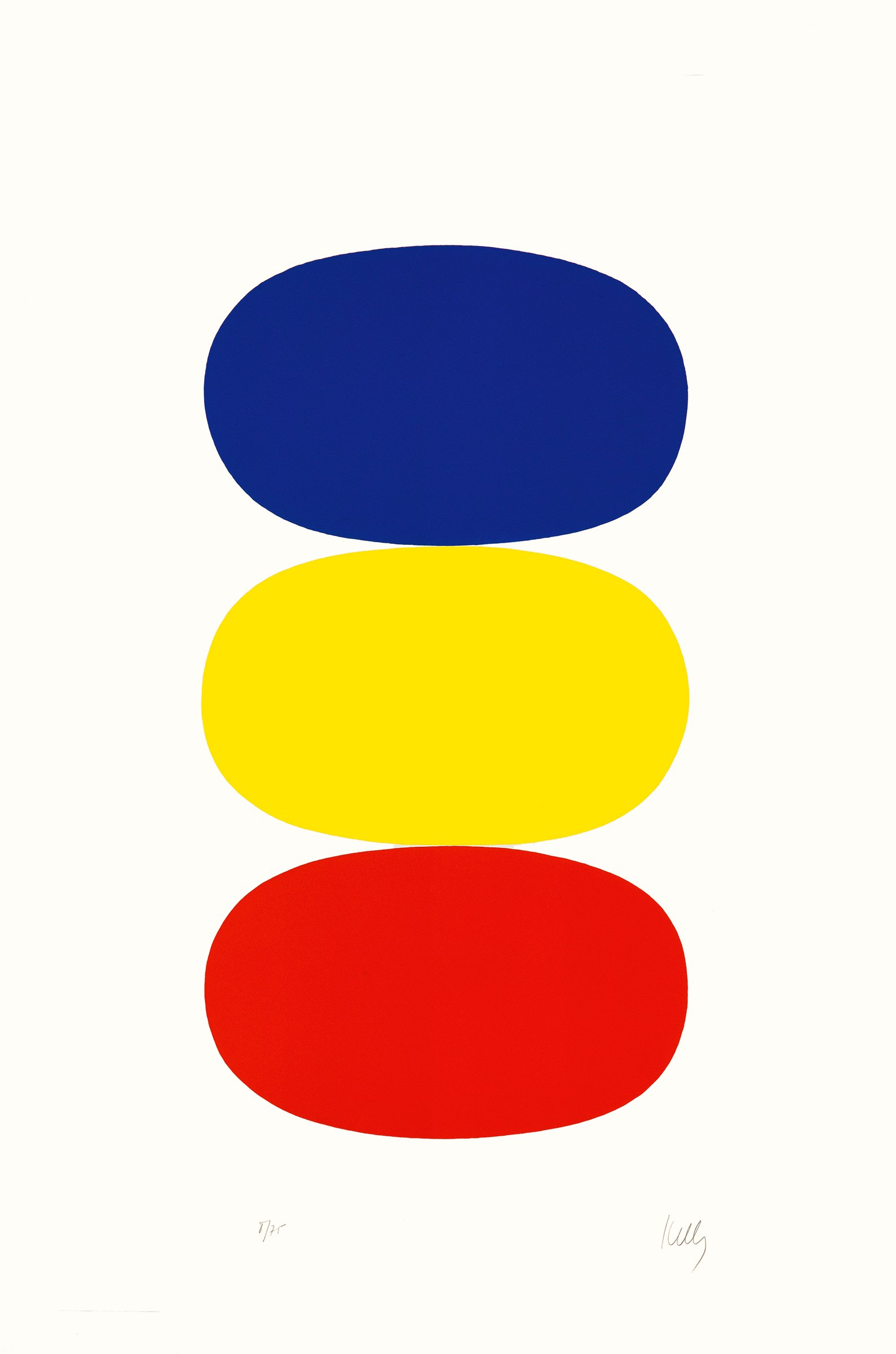

Blue and Yellow and Red-Orange (Bleu et Jaune et Rouge-Orange), 1964-65 by Ellsworth Kelly.

“When people say, ‘Oh, you’ve taken so much out,’ I say I just don’t put it in — and that’s very much a Shaker idea.” Ellsworth Kelly (1923–2015)

The first piece of Shaker handiwork I ever saw was as a teenager, in a friend’s home — though people often see Shaker pieces first in a museum or an antique shop where, I think it’s fair to say, as in someone’s home, the encounter is often contextualized less by the history of this millenarian restorationist Christian sect than by an esthetic narrative endorsed by generations of curators, shopkeepers, and collectors who put Shaker pieces in front of our eyes.

In Kindred Aesthetics, a short film made in 2011 for the Shaker Museum Mt. Lebanon, in New Lebanon, New York, near the home where Ellsworth Kelly lived until his death in 2015, the artist described his own first encounter with Shaker furniture — a long wooden table.

“In 1970, when I moved up to Columbia County, I didn’t have any furniture. When my mother and father came to see me they said, ‘You don’t have chairs to sit down in....’ I didn’t know [the table] was Shaker when I first saw it — it was nearby at an auction at a farmhouse. I saw some people who were talking about it, saying, ‘We should get this one,’ and to myself I said, ‘Oh no you don’t. I am going to get it.’ Friends of mine recognized it immediately. I said, I guess I need more Shaker because I like it. It’s simple very well structured and in the same category as I like to make paintings in.”

That table, which dates from 1835 and served as Kelly’s worktable for the rest of his life, was included in a exhibition at the Jeff Bailey Gallery in Hudson, New York, that combined prints by Kelly with several pieces of Shaker furniture collected by the artist and his longtime partner, photographer Jack Shear, was donated to the Shaker Museum Mt. Lebanon. It was a show in which nothing was for sale. Rather, says Bailey, it was a show “to immerse viewers in an idea.”

Among the works by Kelly in the show were an untitled wedge of blue from the 1980s, displayed near, but not exactly paired with, three Shaker boxes dating from 1830 to 1860. In the same room, the iconic, fan-shaped Red Curve from 1988 was hung in what might be termed “loose dialog” with Kelly’s venerable worktable. The placement of the pieces allowed us the space to contemplate how the artist might have looked at both his work and the possessions he lived with. About a handsome, ca. 1840 side chair in the show Kelly has commented, “The curved forms that make up the back of the chair are shapes I use also. I see them as three curves in front of the white wall — the negative shapes are just as important. It's a very modern idea.”

“He knew nothing about the Shakers when he started buying pieces of Shaker furniture,” Kelly’s partner Jack Shear told me recently. “He bought them because they appealed to his esthetics. They appealed to his sense of measure.”

Shear and Kelly met during the early 1980s, and after a few genial encounters really hit it off. “My vision was sympathetic with Ellsworth’s vision,” says Shear, whose own collection of photographs from the 1840s to today was recently donated to Skidmore College’s Tang Museum and published as a book, Borrowed Light (Prestel). “Our perception of the world and seeing art had a relationship outside of ourselves. He was 60 and I was 30, and I always felt that, in the relationship, later, I was the older of the two. Only because his enthusiasm about looking at the world was amazing! It was literally the wonder that an eleven-year-old boy — you see in their face that kind of recognition…. He said, ‘I want to create things that I’ve never seen.’”

Spit Box, Church Family, Mt Lebanon, NY, ca. 1840.

Polishing Broom, Church Family, Mt Lebanon, NY, ca. 1850.

According to Shear, Kelly derived this sense of esthetic measure — which may be thought of as the relationship between order and complexity — from the years he spent living and working in Paris, in the late 1940s and early ‘50s. “It was intuitive ... classical in a lot of ways. He talked about not having to have a theory like Albers, not having to have a system like Donald Judd.”

Kelly had “a very specific way of looking at the world,” Shear noted. “He wanted his art to function the way objects function in the real world — a chair, a tree, a mountain….”

“Shaker” is a word now often processed through our brains’ design chip, and as such it has influenced the work of design people from Sister Parish to Gio Ponti, largely because of the simplicity and functionality that were key principles of Shaker workmanship, associated with restraint and a taste for the unpretentious: good craftsmanship but nothing fancy or fussy. And happily, the esthetic narrative that developed around Shaker design has functioned as a shimmering protective aura that helps the pieces endure and continue to tell, for those who listen carefully, a deeper story than “form follows function.” And there is a deeper story — about Shaker principles and values, which is currently being explored by the Shaker Museum Mt. Lebanon, among other institutions.

Brick Shop, North Family, Mt. Lebanon, NY, 1829.

Blue with Black I, 1972-74 by Ellsworth Kelly.

“What we sometimes think of in connection with Shaker design is this very stark, modernist esthetic,” the Museum’s Executive Director, Lacy Shutz, told me, on a visit to one of several store rooms packed with Shaker furniture and other objects lovingly stored on massive shelves. “Which is not to say that that esthetic isn't there in its essence. But there were people who came in from outside of Shaker communities to tell a slightly different tale.”

Set among the verdant, rolling hills of Columbia County, the starkly elegant buildings of the Museum’s Shaker village harmonize with their setting as peacefully as a classical temple does in a pastoral landscape by Poussin. But for the Shakers, this harmony was not a matter of “taste.” That concept was far too close to a thing they purposefully avoided as earthly and superfluous: fashion. The Shakers — or the United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing, as they are more properly known — were an offshoot of the Quakers, founded in Manchester, England, in the mid-1700s. The sect was brought to America in 1774, by their leader, Mother Ann Lee, who was accepted by followers as the embodiment of Christ’s second coming. In America the Shakers flourished — first at Mt. Lebanon and then in communities they founded in several states. Aside from the belief that Christ had returned to Earth, the Shakers built a communal life around humility, simplicity, hard work, equality between the genders, and celibacy — the latter practice not only requiring them to proselytize in order to replenish their membership but also distinguishing them from several other 19th-century American religious sects, like the Oneida community, who practiced a form of free love they called “complex marriage,” where anyone was free to have sex with anyone else who consented.

And in a world where the kingdom had come, celibate communal life was an expression of joy and labor a form of praise of God, as was the Shakers’ music and dance. With care they made their furniture, buildings, and garments, believing that making something well was itself an act of prayer. Seeking utility and simplicity, they innovated in craft and farming, yet were perfectly happy to adhere to traditional ways. And early design fanciers did not dismiss this part of the Shaker legacy, exactly.

“Early collectors and photographers started creating these kind of faux interiors where they would position things to reflect a stark modernist esthetic,” noted Shutz. In the first half of the 20th century, photographers like William F. Winter Jr. and influential scholar-collectors like Edward Deming Andrews and his wife Faith E. Andrews, while they cherished Shaker things, were also at pains to codify a Shaker esthetic and align it with clean and hygienic design of the contemporary world.

“But when you see the ad hoc photographs that were taken of Shaker interiors before that,” continued Shutz, “you see these Victorian touches, and it looks like a human being lives there.”

This early-20th-century story of Shaker design was taken up eagerly by academics and good-taste mavens everywhere. Collectors in countries that pioneered modern design, like Denmark and Japan, and as well as in the United States, snapped up pieces and put them under spotlights. By the 1960s, the Metropolitan Museum was actively collecting Shaker furniture and, in the ‘70s, acquired a room from the Mt. Lebanon community. The desire was one part love, one part fetish.

It’s possible that artists and other creative people today are the ones who can best balance the esthetic story of Shaker design with the values and way of life that Shakers have strived for so fervently. In addition to Ellsworth Kelly, Oprah Winfrey, Leo Castelli, David Byrne, and Frances McDormand have all been named as collectors of Shaker objects. McDormand’s connection with Shaker values is perhaps deeper than most, underscored, as it is, by a work of theater that she has been performing in since 2014, parallel to her busy film career: the Wooster Group’s Early Shaker Spirituals, a “record-album interpretation” that recreates a 1976 disc of the same name, of songs, hymns, and marches performed a cappella by the Sisters of the Shaker Community in Sabbathday Lake.

Black Variation II. 1973-75 by Ellsworth Kelly.

Brick Shop, North Family, Mt. Lebanon, NY, 1829.

“We hope to perform our homage to those early Shaker communities until one or all of us drop,” McDormand told me. ”I hope to fabricate an adult-sized cradle, such as they did, so that when one of us becomes too infirm to stand or perform the ritual movements we can continue to sing from our cradle onstage.”

Like many, said McDormand, her first introduction to the Shakers was through their furniture and crafts. “A friend of mine built a Shaker chair from a kit and taught me how to weave the cotton seat and back. The act of doing was meditative and consoling, and I found myself talking out loud to my mother, long gone. I knew she would have been proud and impressed with my handiwork. That chair is one of my prized possessions.”

This is the kind of beauty we feel, that McDormand is describing. But what of the beauty we see, that everybody fetishizes…?

“Beauty is such a tricky word,” Jeff Bailey said. “These are utilitarian objects, made for some kind of use. The Shakers never set out to make a beautiful object, but one that just worked. By making something that works so well, paring it down to its essentials, they arrived at a purity of form that are pleasing to look at, even when they might be a little beat up.”

Yet it is the sheer beauty — some kind of beauty — of these objects that still has the power resonate in a palpable way, some after almost two centuries.

“Ellsworth loved art history,” recalled Jack Shear. “He loved the past and looking at Old Masters, and he got really excited about a lot of things — which is great, because nobody’s excited about anything anymore. And you have this rare person who is enthusiastic about the visual world around him. I would love going to a museum with him because he would see things that you just don't see.”

It is perhaps Kelly’s final creation, Austin (2015), the chapel-like structure on the grounds of the Blanton Museum in Austin, Texas, that best expresses how much his work and Shaker design share resonant “kindred aesthetics.” Kelly, who was an atheist, once explained that inspiration for Austin stems partly from his years in Paris: “I would put my bike on a train and visit early architectural sites all over France. I was intrigued by Romanesque and Byzantine art and architecture. While the simplicity and purity of these forms had a great influence on my art, I conceived this project without a religious program. I hope visitors will experience Austin as a place of calm and light.”

In a way, these two kindred esthetics are doing something more powerful than depicting godliness. Rather than depicting it, the way a Baroque painting of some bloody martyrdom is meant to do, they express the manner in which godliness functions: straight lines and bold colors articulating fortitude, curves connoting the suppleness of true wisdom, finely wrought edges and corners signifying the eternal tension between polarities like good and evil, figure and ground, being and nothingness.

One of the pieces in the “Line and Curve” show was an 1845 work counter, whose left rear corner had been cut way as if to fit closely with some pre-existing structural element of some previous setting. Kelly bought it like that, said Bailey.

“We don't know why it was done, and that’s not a piece that would be sought out because of its perfect finish. But it’s got a story to tell. Here you have an artist who not only strived but perfected this purity of form, based on things observed in the real world. He made it clear that he wasn’t thinking about Shaker when he made anything, but obviously these objects could speak to him because they did have such purity of form.”

Ellsworth Kelly’s work is represented by Matthew Marks Gallery.

Visit The Shaker Museum.

Stephen Greco wrote the live shows Inside Risk: Shadows of Medellin and Peter and the Wolf in Hollywood. His most recent novel is Now and Yesterday published by Kensington.